SCARBOROUGH, Maine — Mark Holmquist proudly wears the uniform as the police chief in Scarborough. He’s been leading the 40-person department for about two and a half years after a 24-year career as a Maine state trooper.

Despite more than a quarter-century as a police officer, some of Holmquist’s most lasting memories are of his time in a U.S. Army dress uniform as a guard, also called a sentinel, at Arlington National Cemetery and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

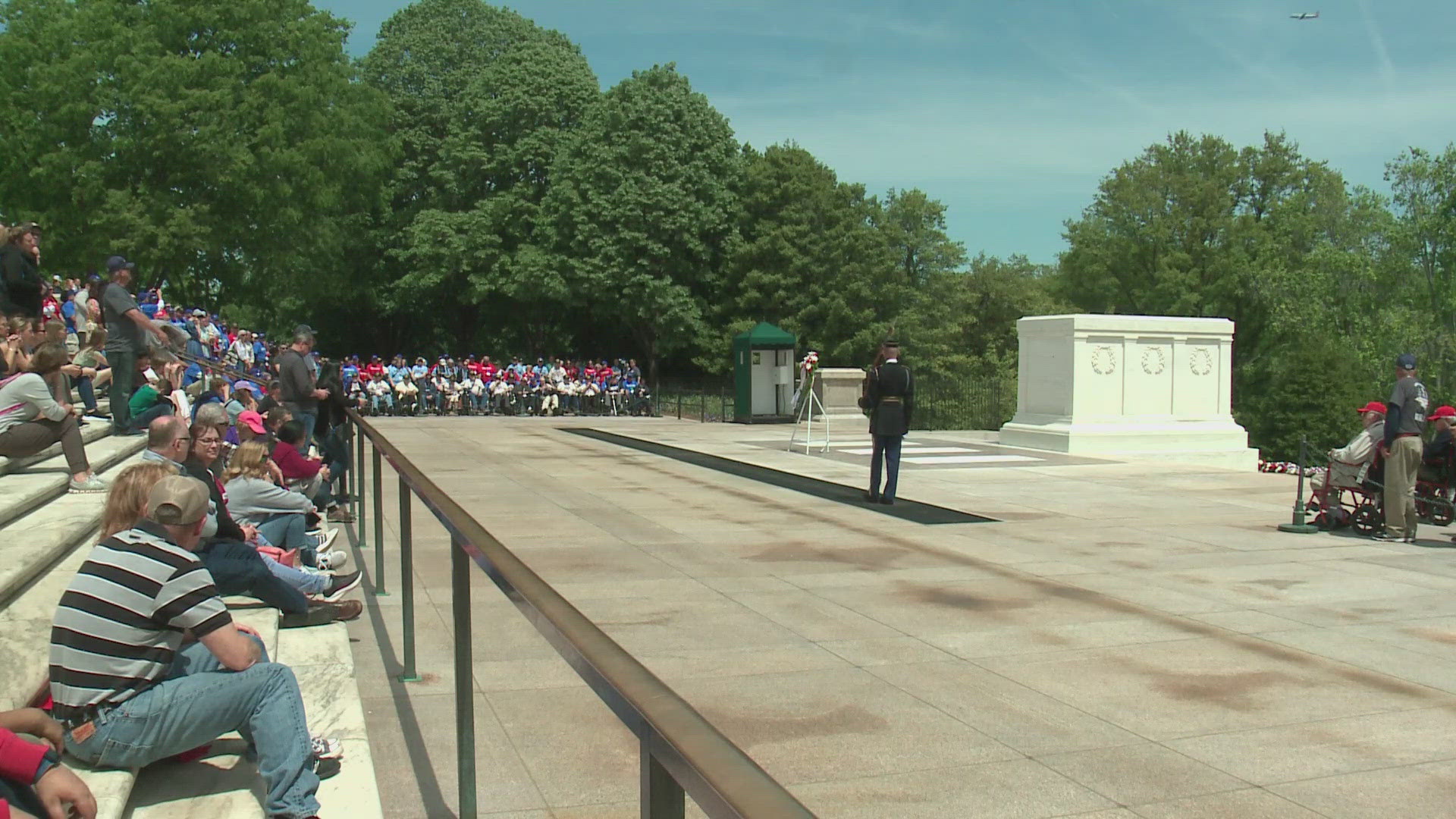

Holmquist said he first saw the sentinels perform the changing of the guard ceremony when he was an 18-year-old Army private.

“And when I watched the soldier walk across the mat at the tomb, I saw how professional that soldier appeared to be, and at that moment I decided I wanted to be a tomb guard,” Holmquist recalled.

He was in the right place to volunteer for that duty. Just two or three days into his basic training, Holmquist was chosen to join the Army division called the “Old Guard,” which handles ceremonial duties in Washington, D.C., and funerals at Arlington.

Holmquist said he was picked out because of height, appearance, and having what was called a “military bearing."

Those same qualities were needed to be a tomb guard, so he took the test and was accepted—knowing that he faced months of additional physical and mental training that’s required for those elite positions.

“The standard at the tomb, in line six of the creed, says my standard will be perfection," he said. "And we all know you can’t attain perfection, it's unreasonable to ask but for the Unknowns, we try each and every day to get as close to what perfection looks like."

The first months of training, he said, were rigorous. The recruits had to learn the special way of marching the guards use when at the Tomb, stepping first with the toe and rolling the foot along smoothly so that there is none of the normal up-and-down motion of the body in normal marching or walking.

“The key is not to bounce when you march,” he explained. “So when people ask me what do you think about when you march, did it get boring? It didn’t, because I was consciously evaluating each and every step. Every step, I’m watching my visor to see if there is any bounce to the visor. I’m listening to the bayonet on the rifle, If I can hear the bayonet making any noise, I know I’m bouncing or my arm position isn’t right.”

That precision, he said, had to be matched by studying and memorizing much of the history of Arlington and the Tomb, as well as the creed and other guidelines for guards.

“There were upwards of 10 poems we had to memorize and be able to recite, had to know 100 locations of people buried at Arlington deemed prominent, and also know where they were buried," he said. "So on days off, I’d be walking around walking around, trying to find locations. That didn’t happen on duty days, it was off time.”

The rookie sentinels also had to learn how to prepare their uniforms to exacting standards. That work, Holmquist said, is not done by a dry cleaner: “It was done by us. So we spend a lot of time basically in a press shop down in the basement with an industrial press, making sure the pleats in the back of the uniform, that we put in ourselves, were tailored to our bodies. Make sure those were right on target.”

The same standard applied to constantly polishing all the brass on the uniforms, and cleaning and maintaining the rifle.

Those uniforms have no insignia of rank or stripes. Holmquist said that since the rank of those in the Tomb is not known, the sentinels show no rank themselves.

The total spit and polish, the precision of the march, the rifle handling—all are intended, he said, to show honor to those resting in the Tomb.

“A lot of detail, attention to detail is everything there, but it's for a good reason," he said. "It's for the unknown soldiers who gave too much.”

For that same reason, he said, the precision of the changing of the guard ceremony is centered on the number 21, symbolic of the 21-gun salute.

“(It's) the highest honor you can give a military member who has given their life," he said. "Everything is based on 21. So 21 steps on the mat when you march in one direction. Stop, face the tomb, and wait 21 seconds. Once that is completed face back down the mat, do a shoulder change of the weapon. Once that is completed, wait 21 seconds, then walk down the mat another 21 steps.”

The changing of the guard ceremony happens every half-hour in the summer and every hour in winter—basically all the hours that Arlington is open to the public. When the cemetery is closed, the sentinels continue to guard the Tomb but do not perform the elaborate changing ceremony. Instead, he says the sentinels change to typical Army fatigues and patrol the tomb area in other ways, to ensure the Tomb is never vandalized.

It is a rigorous schedule. The 27 guards are divided into three units, called "reliefs," and each relief is on duty for a 24-hour period. But off-duty time, Holmquist said, is often consumed by training, study, and preparation.

Holmquist served 14 months as a Tomb guard until he was discharged from the Army. He earned the coveted badge for that position, based on performance and testing. The badge also allowed him to take charge of the changing of the guard, handle inspections, and other duties.

The badge is something that stays with a Tomb guard for life and can also be revoked if the individual does something later in life deemed to dishonor the unknown soldiers.

Holmquist still proudly has his badge and often gives talks and presentations about the work and traditions of the Tomb guards.

He still shares the story of a day on duty, in the rain, guarding the Tomb, when a man came up in a wheelchair.

"A double-amputee," he said. "And he had a flag attached to the back of the wheelchair and wearing a Vietnam Veterans hat. And he came up and centered himself by the Vietnam unknown.

“And the most impressive thing was he didn’t have a raincoat on, no coat but he was there to honor his friend. And so I walked back and forth in front a few times and heard he was emotional, sobbing. And the last time I marched by, he rendered a hand, saluted, and said thank you for taking care of my friend. And at that moment I knew exactly why I was a tomb guard, and how important it was not only for me but everyone who visited."