BOSTON (NEWS CENTER Maine) – A revolutionary medical program in New England is saving lives, but comes with a dark cost.

Doctors at Mass General Hospital in Boston have found a way to save more lives using kidneys coming from donors who died from a drug overdose.

The opioid epidemic killed more than 64,000 Americans – including more than 400 Mainers – last year.

From 2010 to 2016, there was a 277 percent increase in kidney donors who died from overdoses. About 1 in 5 of those donors are infected with Hepatitis C (HCV), a virus commonly spread by needle use.

Doctors at Mass General have been transplanting HCV positive kidneys to HCV positive recipients for a long time. They’ve only recently discovered that they can safely transplant those infected kidneys into a patient without Hepatitis C.

This is a game changer in the medical industry and reduces the wait time for kidneys in New England from around 6 years to in some cases just weeks.

For Jason Lytle of North Providence, Rhode Island, the program made a lifetime of difference.

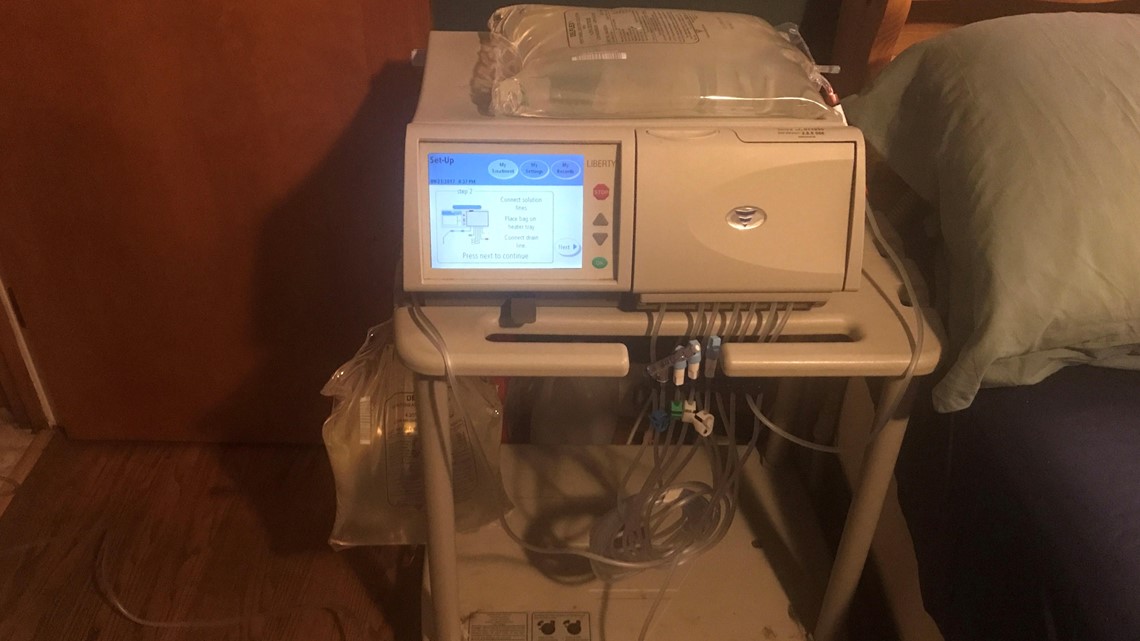

He had waited two years for a kidney. That’s two years of dialysis at his home, and two years of lacking the energy to play with his 4-year-old daughter.

“The boxes of fluid that I use [for dialysis], each box weighs about 40 pounds…and they would deliver about 50 to 60 boxes each month,” he said of the two-year ordeal.

With 900 pounds of fluid sitting in his home, waiting to go into his body - Jason was willing to try anything to get a kidney.

So when he found out about Mass General's new protocol of transplanting Hepatitis-C positive kidneys - he signed up immediately.

That willingness to participate from Jason and other patients surprised Mass General nephrologist Dr. David Wojciechowski. “We thought for sure that would be our biggest hurdle to consenting patients for this protocol,” he said. “I think the what we have found is that patients seem less worried about [the HCV risk] than I think we were worried about.”

Within two weeks and after one false alarm, Jason Lytle had a kidney ready for him.

This process is possible because there are a number of drugs on the market that can cure Hepatitis C, which weren’t around years ago.

The unique factor of Mass General’s program is that doctors start treating organ recipients with these drugs before they transplant the infected kidney to make sure the virus never fully manifests.

Jason remembers when he took his first pill to prevent and treat HCV. “As they are pushing my bed down to the operating room, that's when they handed me the first pill,” he said.

Patients – including Jason – often see a small flare of the virus in the first few days, but it has gone away completely in every patient that has received one of these kidneys in the last 8 months.

Dr. David Wojciechowski says the hospital is monitoring its patients for both the short-term and long-term effects of this procedure.

The challenge for recipients is grappling with the reality of where that kidney came from. These kidneys are likely a result of New England's ever growing opioid epidemic. “That is another public health crisis that need to be addressed,” Dr. Wojciechowski says. “But I think when you have something like that occur, I think it always helps to find some positive way to turn that around it to get something positive out of it. So I think in transplantation we've been able to do that.”

According to a study by Mass General researchers, donors who die from drug overdose and donors with HCV are “younger, less likely to have diabetes or hypertension, and have favorable kidney donor profile index scores compared to average donors.”

Since his transplant, Jason Lytle's kidney function is better than it's ever been.

He has the energy to play with his daughter again.

He knows he'll be around to see her go to prom, to graduate. “I now know that I'm going to be around for those things,” he said with a smile on his face. “I thought about the other day and I started crying. I'm going to get to walk her down the aisle.”

Jason can't find the words to thank the family that saved his life, or the words to console them for their loss.

It's something he's struggled with since he got his new kidney on August 3rd. “If they had to lose a child so that my daughter can have her father… I do want to thank that family. I've got to find the right way to do it,” he said as he fought back tears.

Jason doesn't know who he got his kidney from.

When he's ready, he says he'll write a letter to the family that Mass General will deliver.

Could a program like this come to Maine? Dr. Wojciechowski says he warns any department to make sure it is equipped with all the necessary researchers and resources before starting a program like this.

He says before starting its program, Mass General consulted with two other hospitals with similar programs.